Integrated Custom File Processors

The features in this article were added in Data Import 1.2. They enhance and extend prior versions' Integrated Custom Record Processing and Integrated Custom File Generation features.

Overview

Data Import is not a catch-all extract-transform-load (ETL) tool as one may find with commercial applications. Boomi, Microsoft Biztalk, Oracle Weblogic and Talend are examples of ETL applications (ranging from open source to on-premises to SaaS) that may be used to accommodate loading of legacy data sources into the Ed-Fi ODS / API.

Data Import is a data mapping and data loading tool for the ODS / API. CSV fields are mapped to ODS / API fields, so that a CSV input file can be iterated over and POST-ed to the ODS / API resource endpoints. Still, there are some ETL-style needs which present as obstacles to simple mapping. Data Import includes PowerShell preprocessor support in service of these needs.

Before opting into this feature, consider: is your scenario an aspect of data mapping itself, or an ETL process better served prior to mapping?

Examples of mapping challenges served by PowerShell preprocessors:

- Simple 'clean up' of individual values such as trimming excess space or reformatting dates.

- Importing from non-CSV files (tab-delimited, fixed-width, ...).

- Reshaping of the row 'grain' of the input file (one row becomes multiple rows or vice-versa).

- Skipping input rows (e.g. student assessment rows that indicate the student was not tested).

- Performing API calls against the target ODS / API.

3 Kinds of Preprocessor Scripts

Prior versions of Data Import introduced support for 2 kinds of PowerShell preprocessor scripts:

- Custom Row Processors

- Optionally selected on the Agent screen.

- The script is invoked once per input row, with the opportunity to inspect and modify each row one at a time.

- As an aspect of your Agent, rather than as an aspect of a Data Map, these are not shared.

- As a general rule, we recommend upgrading these to work with the new "Custom File Processor" scripts described below, for additional flexibility, sharing, and diagnostic logging.

- Custom File Generators

- Optionally selected as the type of Agent on the Agent screen. Rather than working with a preexisting file, the Agent produces its own file with a script and then proceeds with mapping/importing.

- These tend to require exceptional access to the server's capabilities in order to perform database queries and to access the filesystem directly.

- Using a File Generator is a strong indicator that you are mixing Data Import's data mapping role with the ETL role of other systems. Consider: does Data Import need to know about your bespoke ETL scripting prior to mapping and importing?

Data Import adds a third type of preprocessor script:

- Custom File Processors

- Optionally selected on the Data Map screen.

- As they are an aspect of a Data Map, these are naturally shared with Data Maps via Import / Export and the Template Sharing Service.

- Can perform API calls against the ODS / API during data load. Data Import manages your Key and Secret, as well as Access Tokens, to ease access to the API.

- Enhanced logging support: scripts can log diagnostic information during execution, useful when debugging scripts.

PowerShell "Sandboxing" Security

Data Import is not a programming language. Data Import is not an ETL tool. Data Import is a data mapping tool which posts to the ODS / API.

As of Data Import 1.2, preprocessor scripts run in a safe-by-default PowerShell "sandbox". The core language is available, as well as many common built-in operations and ODS / API specific commands, but all potentially-dangerous operations are locked down by default. A malicious script author, for instance, would want to cause harm by accessing the filesystem directly, by attempting to connect to databases on the local network, etc. The sandbox is safe by default, so all such attempts would rightly fail for them at runtime.

Danger

This sandboxing safety can naturally pose a problem when your script needs to do something like access the filesystem or query databases. File Generators, for instance, perform exactly that kind of work by their very nature. This is a good reason to question whether such an operation belongs inside a data mapping step within a data mapping tool, rather than inside an ETL process prior to mapping with Data Import.

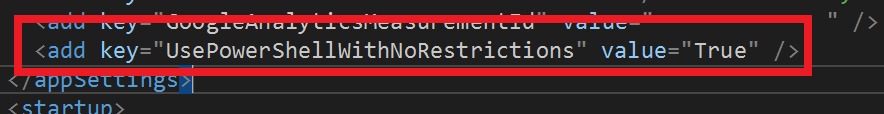

If an administrator wants to opt-in to the risks of arbitrary code running in their data maps, performing file access, database connections, and the like, they can enable full access to the PowerShell language and commands: in both the DataImport.Web/Web.config file and the DataImport.Server.TransformLoad/DataImport.Server.TransformLoad.exe.config file, locate the <appSettings> tag and add the following setting to enable full PowerShell access:

Custom File Processors - Examples

The rest of this page focuses on modern Custom File Processors. For more on Row Processors and File Generators, see:

All of the examples in this page are based on the Student Assessments example described in the Quick Start.

All of the example templates and example input files are in the attached zip. The *.json template files can all be imported into a test Data Import installation, and then tested using Manual Agents with the sample *.csv and *.txt files enclosed in the same zip.

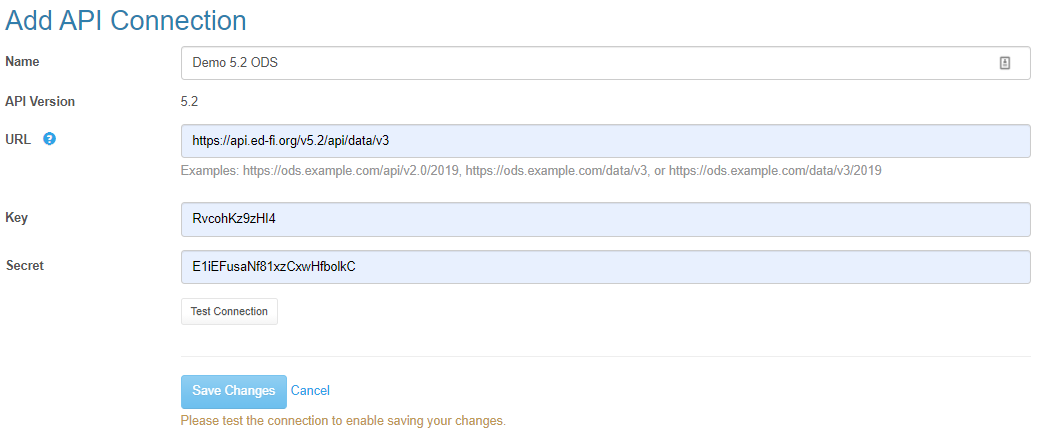

They are all intended to work against an ODS with the "Grand Bend" sample data as a prerequisite, such as for the public instances hosted on https://api.ed-fi.org/:

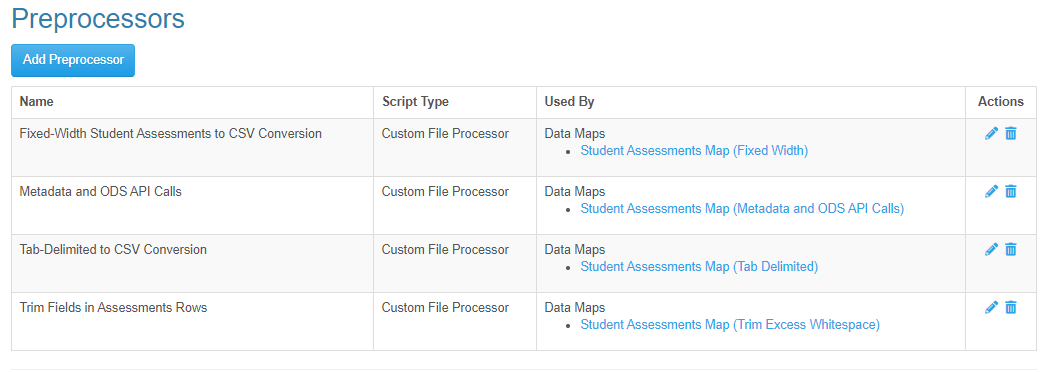

After importing the sample *.json templates found in the attached zip file, you'll have several similar Data Maps, Bootstraps, and most interestingly Preprocessors:

Example: Tab-Delimited Files

Template to Import: ODS 5.2 Student Assessments - Tab Delimited.json

File to Upload: DI-QA-STUDENT-ASSESSMENTS-2018-GrandBend - Tab Delimited.txt

Let's start simple. We have a file where the individual values are not separated by commas, but instead by wide 'tab' characters. See for yourself: open the file in a simple text editor like Windows' Notepad and move along the contents of each line. You'll find that the gaps between values are not multiple spaces, but instead single wide tab characters.

By default, Data Import works with Comma-Separated Value (CSV) files, so on its own, this file will be meaningless to Data Import. However, the Data Map in this template includes its own Preprocessor to convert each line from being tab-delimited to a valid CSV:

[CmdletBinding()]

Param(

[Parameter(Mandatory = $true, ValueFromPipeline = $true)][string]$line

)

Begin {

Write-Information "Converting tabs to commas"

}

Process {

Write-Output $line.Replace("`t", ",")

}

End {

Write-Information "Finished converting tabs to commas"

}

Here, we see the basic structure of a 'Custom File Processor' script. Custom File Processors begin like so (it's best to copy this directly to avoid typos and get off to a good start!):

[CmdletBinding()]

Param(

[Parameter(Mandatory = $true, ValueFromPipeline = $true)][string]$line

)

This opening set of lines indicates that we will be receiving and processing the original tab-delimited file one line at a time, and in the rest of our script we will be able to refer to the current line using the variable $line.

Next, we see the script is made of three blocks: Begin, Process, and End. As a PowerShell Advanced Function, the instructions in the Begin and End blocks each run once at the start and end of the execution. The Process block will run many times, once per line (accessed via $line).

You can output diagnostic information with built-in PowerShell commands Write-Information and Write-Host. You can report errors either by using throw or by using the build-in PowerShell command Write-Error. We'll see more on error handling in another example below.

The core logic in our script, then, is the single line within Process: take the original input file line, replace all tabs ("`t" in PowerShell terminology) with commas and then output the result.

While the other Write-* commands output mere diagnostic information to the log at runtime, Write-Output is special. Anything we output with Write-Output indicates the new contents of the resulting CSV file to be processed, mapped, and POST-ed to the ODS / API.

Example: Fixed-Width Files

Template to Import: ODS 5.2 Student Assessments - Fixed Width.json

File to Upload: DI-QA-STUDENT-ASSESSMENTS-2018-GrandBend - Fixed Width.txt

In this example, we deal with a "Fixed Width Field" file. Although strongly discouraged as difficult to work with reliably, some third-party systems export their data as files where each field is understood to exist at certain specific (fixed) character positions. For instance, such a file might be understood to have a field "Student Name" beginning at exactly the 134th character in a line, extending to exactly the 151st character of the line, etc.

Open this sample *.txt file and contrast it with the tab-delimited file of the previous example. Note that this time there are no wide tab characters. Instead, every field is carefully spaced out with individual spaces to fit a particular predefined understanding of where each field begins and ends. The only way to make sense of this during import is to explicitly chop up each line based on the exact start position of each expected field. This can be quite painful to do oneself, so Data Import provides a convenient command ConvertFrom-FixedWidth to assist with the chopping-up of each line:

[CmdletBinding()]

Param(

[Parameter(Mandatory = $true, ValueFromPipeline = $true)][string]$line

)

Begin {

Write-Host "Converting fixed-width fields to commas"

# Zero-based start position of each fixed-width column

$fieldMap = @(

0 # adminyear

11 # DistrictNumber

26 # DistrictName

44 # SchoolNumber

58 # SchoolName

89 # sasid

97 # listeningss_adj

114 # speakingss_adj

130 # readingss_adj

145 # writingss_adj

160 # comprehensionss_adj

181 # oralss_adj

193 # literacyss_adj

209 # Overallss_adj

)

}

Process {

$fieldsFromLine = ConvertFrom-FixedWidth -FixedWidthString $line -FieldMap $fieldMap

$formattedFields = @($fieldsFromLine | % { "`"" + $_.Replace("`"", "`"`"") + "`"" })

Write-Output ([System.String]::Join(",", $formattedFields))

}

End {

Write-Host "Finished converting fixed-width fields to commas"

}

Again, our goal is to first make sense of the incoming $line, calculated the equivalent CSV line, and then use Write-Output to emit that new CSV line.

ConvertFrom-FixedWidth makes use of our $fieldMap positions, producing a simple string array $fieldsFromLine. Now it's our job to reassemble those individual values as a comma-separated line.

Naive implementations would simply perform Write-Output ([System.String]::Join(",", $fieldsFromLine)), but there are extra concerns here for a valid CSV format. What if, for example, one of the District Names in the original fixed-width file happens to contain a comma as well? Our result would be incorrect, and Data Import would have no way of knowing that the comma was part of a value. Data Import would have no choice but to treat the comma as a field-delimiter like all the rest!

Wise implementations instead take extra care regarding quotations marks and commas when taking the original values returned to us by ConvertFrom-FixedWidth and producing our output CSV line. The middle statement in our Process block performs the following work on each individual value in the row:

- Take any occurrence of special character " (a single character indicating double-quote), and replace it with two in a row: "".

- This is the proper CSV format indication that a double-quote character *is a part of a value*.

- Take that and surround the entire value with its own pair of "double quotes" so there is no mistaking where it begins and ends.

Now, our Write-Output of those $formattedFields is safe: it produces valid CSV lines even if the original fixed-width file contained meaningful commas or quotes in their values.

Example: Cleaning Individual CSV Cells

Template to Import: ODS 5.2 Student Assessments - Trim Excess Whitespace.json

File to Upload: DI-QA-STUDENT-ASSESSMENTS-2018-GrandBend - With Excess Whitespace.csv

In this example, we begin with a valid CSV file, but some of the values appear to be quite "padded" with extra spaces. Attempting to import this data without a preprocessor, the ODS / API is surely going to reject our data as invalid for some fields. For some fields, the ODS / API absolutely and rightly demands that only digits be provided, and the extra spaces here would appear to be a gross error on the part of the user. Data Import will not assume that it can change your values away from those given. So, we'll need to use a preprocessor to inspect, clean up, and then emit each value as intended:

[CmdletBinding()]

Param(

[Parameter(Mandatory = $true, ValueFromPipeline = $true)][string]$line

)

Begin {

$header = "adminyear,DistrictNumber,DistrictName,SchoolNumber,SchoolName,sasid,listeningss_adj,speakingss_adj,readingss_adj,writingss_adj,comprehensionss_adj,oralss_adj,literacyss_adj,Overallss_adj".Split(",")

}

Process {

Write-Host "Original Line: $line"

# Parse the single line into an object with key/value pairs.

$row = $line | ConvertFrom-Csv -Header $header

$row.'sasid' = $row.'sasid'.Trim()

$row.'Overallss_adj' = $row.'Overallss_adj'.Trim()

# Serialize the row object back into comma-separated format.

# Item [0] is the headers, so we skip to item [1] the single row of the intermediate CSV.

$trimmedLine = ($row | ConvertTo-Csv -NoTypeInformation)[1]

Write-Host "Trimmed Line: $trimmedLine"

Write-Output $trimmedLine

}

PowerShell does include a handy pair of functions, ConvertFrom-Csv and ConvertTo-Csv, but they have some unfortunate limitations: they generally wish to be working with a whole file at once rather than individual lines. So, here we make use of them carefully to work with our individual $line anyway. First, we use the -Header option when reading the $line so that we can get access to a rich $row. Here, $row has access to all of the values of the row, accessible with via the column headers. We interact directly with our two problematic columns' values, accessing them by name ('sasid' and 'Overallss_adj'), trimming away excess spaces.

But our work is not done! Our rich $row has all the right values in it, but our job is to Write-Output in CSV format. Unfortunately, ConvertTo-Csv needs some extra help to know what we're asking for here. On its own, it would output two lines: the headers at position [0] (which we don't need again, we've already output them by this point!), and the line we're interested in at position [1]. We grab that interesting safely-formatted CSV line from position [1] and output that.

Example: Metadata and API Calls

Template to Import: ODS 5.2 Student Assessments - Metadata and ODS API Calls.json

File to Upload: DI-QA-STUDENT-ASSESSMENTS-2018-GrandBend.csv

File Processor Scripts have access to extra "metadata" about the current execution, and that includes sufficient information to perform API calls against the ODS / API on your behalf.

The basic metadata values available to you at runtime are:

- MapAttribute: An optional text value set on the Data Map screen. If you're using the same script against multiple different maps, for instance, each map might use this to identify itself. Your script might perform different work depending on the value you receive here.

- Be sure to enable this if you wish to use it: on the Preprocessor screen, check "Script expects a data map attribute to be supplied".

- PreviewFlag: This is a boolean value (true or false), indicating whether the script is running for the purposes of a preview. When working with a preprocessor-enhanced Data Map, the Data Map editor screen allows you to upload a representative file for processing and display in the editor. Some scripts may wish to behave slightly differently depending on whether they are really performing a data load, or merely being used in such a preview run.

- Filename: The file name being processed

$lineby$line. - ApiVersion: The version of the ODS / API being loaded.

Scripts can make API calls against the target ODS / API as well.

- Be sure to enable this if you wish to use it: on the Preprocessor screen, check "Script uses Invoke-OdsApiRequest for ODS API access".

Data Import manages all of the connectivity here, allowing you to focus on the work of interacting with the ODS resources. Our example script this time makes no changes to the original file (it merely "echoes" each original $line to the output), but before doing that work it performs many API calls in order to output live Descriptor values as a sort of diagnostic first:

[CmdletBinding()]

Param(

[Parameter(Mandatory = $true, ValueFromPipeline = $true)][string]$line

)

Begin {

# This demonstrates some of the contextual information and

# API-calling capabilities of PowerShell scripting.

# Scripts have access to contextual information:

Write-Host "Map Attribute: $($DataImport.MapAttribute)"

Write-Host "Preview Flag (true during previews in the Data Map editor): $($DataImport.PreviewFlag)"

Write-Host "Filename: $($DataImport.Filename)"

Write-Host "API Version: $($DataImport.ApiVersion)"

# Scripts can perform API calls against the ODS:

try {

Write-Host "Attempting an API call that we expect to fail due to 404 (File Not Found)"

$response = Invoke-OdsApiRequest -RequestPath "/missing-extension/missing-resource"

} catch {

Write-Host "The API call failed: $_"

Write-Host "Since this failure was expected, we allow execution to continue..."

}

Write-Host "Using Invoke-OdsApiRequest to fetch preexisting GradeLevelDescriptors..."

$continue = $true

$offset = 0

$limit = 10

$descriptorNumber=0

while ($continue) {

Write-Host "Fetching GradeLevelDescriptors with offset=$($offset) and limit=$($limit)..."

try {

$response = Invoke-OdsApiRequest -RequestPath "/ed-fi/gradeLevelDescriptors?offset=$offset&limit=$limit"

} catch {

# At this point we are in an unexpected situation, and throw in order to halt execution.

Write-Error "Halting execution. An API call failed unexpectedly: $_"

throw $_

}

Write-Host "HTTP Status Code: $($response.StatusCode)"

foreach ($key in $response.Headers.Keys) {

Write-Host "HTTP Header '$key': $($response.Headers[$key])"

}

$descriptors = ConvertFrom-Json $response

if ($descriptors.Count -gt 0) {

Write-Host "Received $($descriptors.Count) GradeLevelDescriptors for this request:"

foreach ($descriptor in $descriptors) {

$descriptorNumber = $descriptorNumber + 1

Write-Host "$($descriptorNumber): $($descriptor.namespace)#$($descriptor.CodeValue)"

}

}

else {

Write-Host "Received 0 GradeLevelDescriptors for this request, indicating the end of paged fetching."

$continue = $false

}

$offset += $limit

}

Write-Host "Using Invoke-OdsApiRestMethod to fetch preexisting GradeLevelDescriptors..."

$continue = $true

$offset = 0

$limit = 10

$descriptorNumber=0

while ($continue) {

Write-Host "Fetching GradeLevelDescriptors with offset=$($offset) and limit=$($limit)..."

try {

$descriptors = Invoke-OdsApiRestMethod -RequestPath "/ed-fi/gradeLevelDescriptors?offset=$offset&limit=$limit"

} catch {

# At this point we are in an unexpected situation, and throw in order to halt execution.

Write-Error "Halting execution. An API call failed unexpectedly: $_"

throw $_

}

if ($descriptors.Count -gt 0) {

Write-Host "Received $($descriptors.Count) GradeLevelDescriptors for this request:"

foreach ($descriptor in $descriptors) {

$descriptorNumber = $descriptorNumber + 1

Write-Host "$($descriptorNumber): $($descriptor.namespace)#$($descriptor.CodeValue)"

}

}

else {

Write-Host "Received 0 GradeLevelDescriptors for this request, indicating the end of paged fetching."

$continue = $false

}

$offset += $limit

}

}

Process {

# This script makes no changes to the file content itself. Its purpose is entirely to demonstrate the

# behaviors used in the "Begin" section above.

Write-Output $line

}

Here we see two similar ways of interacting with the API:

1. Invoke-OdsApiRequest whose behavior matches that of built-in Invoke-WebRequest while managing URLs and authentication on your behalf.

2. Invoke-OdsApiRestMethod whose behavior matches that of built-in Invoke-RestMethod while managing URLs and authentication on your behalf.

Most users will simply want to use Invoke-OdsApiRestMethod as it is simpler to work with when you are primarily interested in inspecting the Content of the ODS / API's HTTP response. It considers the HTTP headers and body content for you, so that you get back a rich object corresponding with the JSON payload received.

Some users may wish to have more direct access to the full HTTP response, including its StatusCode, Headers, and Content. In order to then interact with a rich object for the JSON payload, such users will need to perform the extra JSON-to-object step themselves: ConvertFrom-Json $response

Error Handling

In the "Metadata and API Calls" we see examples of proper error handling. In general, PowerShell tends to keep moving when it encounters an error. That can be problematic if you run into a severe error and proceeding would be meaningless, risky, or have unpredictable results.

In order to take control, we strongly recommend using try/catch blocks and throw explicitly when appropriate. Especially around each API call such as in the example, wrap the attempt in try/catch. Depending on your situation, you may decide to proceed or fail the run immediately. To proceed, simply allow control to flow beyond the catch block as as in the example's "expected 404". To fail the run immediately without proceeding, exit with throw $_, ensuring that execution stops and that the error details arrive in the log.